- Air Operations - General

- Definitions

- Part-ARO

- Part-ORO

- Passenger Safety

- Part-CAT

- Part-SPA

- Dangerous Goods

- Part-NCC/NCO

- Part-SPO

- Helicopter operations

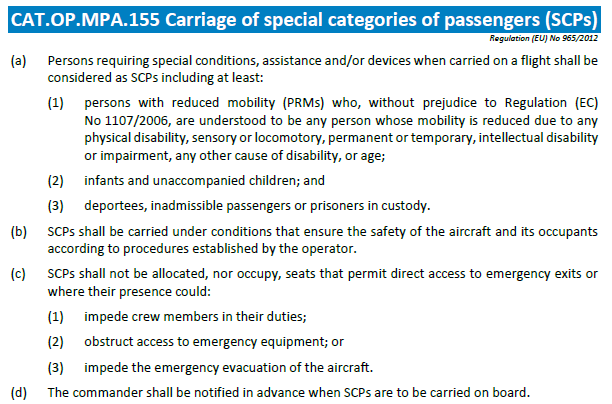

- Special Categories of Passengers (SCPs)

In case the answer you were looking for in this FAQ section is not available: you might submit your enquiry here

Air Operations - General

In the definition of ‘commercial operation’ published in Art. 2 of Regulation (EU) 965/2012 (introduced by the amending Reg. (EU) 2018/1975), what is the meaning of the term “control”?

Reference: Reg. (EU) 965/2012, Article 2:

‘“commercial operation” shall mean any operation of an aircraft, in return for remuneration or other valuable consideration, which is available to the public or, when not made available to the public, which is performed under a contract between an operator and a customer, where the latter has no control over the operator.’

Pursuant to Article 140(2)(a) of Regulation (EU) 2018/1139 (the New Basic Regulation), ‘commercial operation’ shall still be understood as a reference to point (i) of Article 3 of Regulation (EC) No 216/2008. This is a transitional provision until not later than 12 September 2023, when the implementing rules adopted on the basis of Regulations (EC) No 216/2008 and (EC) No 552/2004 shall be adapted to this Regulation. The same definition of ‘commercial operation’ has already been transposed in Article 2 of Reg. (EU) No 965/2012 on air operations and is applicable as of 9 July 2019.

Would there be a restriction that requires baby bassinets to be removed and stowed during in-flight turbulent weather conditions? Where is it documented?

Reference: CS-25 (Large Aeroplanes)

Baby bassinets are currently included in a certification process of the particular aircraft in which they will be installed; baby bassinets are not certified as a separate device and they are not certified for taxi, take-off, landing and turbulent weather conditions. Placards advising on their stowage during taxi, take-off, landing and turbulence are required either at the location where baby bassinets will be fixed to the aircraft structure (e.g. bulkhead) or a clearly visible instruction advising on the same must be in place on the baby bassinet itself.

Because of the standard fixation of the unit, they are not stable during turbulence, they may swing up and down, and therefore they must be stowed during turbulence.

The placarding requirements are related to the general certification requirements on placarding and intended function in accordance with Certifications Specifications and Acceptable Means of Compliance for Large Aeroplanes CS-25 (ED Decision 2012/008/R) and the marking requirements as specified in the approval of the equipment. The applicable reference paragraph is CS 25.1301, 25.1541. There is no specific mention of baby bassinets, however, equipment installed in an aircraft must meet the applicable requirements of the certification basis, the equipment specifications (if available) or aircraft manufacturer specifications (if available), or NAA requirements applicable to the operation of the aircraft.

For any questions on certification matters, do not hesitate to contact EASA Certification directorate.

What are the essential requirements?

Reference: Regulation (EU) 2018/1139, Regulation (EU) No 965/2012 on Air Operations

Essential requirements are high-level safety objectives and obligations put on persons and organisations undertaking aviation activities under Regulation (EU) 2018/1139 (the Basic Regulation). Detailed rules are then adopted by the European Commission based on technical advice from EASA to further detail how to achieve these objectives and obligations. For example, the implementing rules for air operations (i.e. Reg. (EU) No 965/2012) have been developed in order to ensure uniform implementation of essential requirements related to air operations.

The Basic Regulation has annexes containing essential requirements for:

- airworthiness (Annex II),

- environmental compatibility related to products (Annex III)

- aircrew (Annex IV),

- air operations (Annex V),

- qualified entities (Annex VI),

- aerodromes (Annex VII),

- ATM/ANS and air traffic controllers (Annex VIII), and

- unmanned aircraft (Annex IX).

The Essential Requirements can be amended by the European Commission where necessary for reasons of technical, operational or scientific developments or evidence.

What do 'grandfathering', 'transition measure' and 'opt-out' mean?

Reference: Regulation (EU) No 1178/2011, Regulation (EU) No 965/2012

These terms refer to certain legal concepts used in aviation safety regulations, in particular Reg. (EU) No 1178/2011 on aircrew and Reg. (EU) No 965/2012 on air operations.

'Grandfathering' designates the legal recognition and acceptance of certificates issued on the basis of national legislation by national authorities prior to the entry into force of a specific regulation. For example, in Reg. (EU) No 1178/2011, the conditions for the grandfathering of JAR-compliant and non-JAR-compliant pilot licences and medical certificates are set forth in its Articles 4 and 5. In Reg. (EU) No 965/2012, the conditions for grandfathering of EU-OPS AOCs are set forth in Article 7(1).

Grandfathering measures are included in the Cover Regulation to assist Member States in the transition from national rules to unified EU rules. In the case of aircrew licensing, provisions on grandfathering consider some national certificates issued in compliance with given regulations and by a certain date as being in compliance with the new Aircrew Regulation (i.e. Reg. (EU) No 1178/2011).

A 'transition measure' is a provision helping the national competent authorities and regulated entities to gradually adapt to the new EU rules. Several examples can be found in the Aircrew Regulation, such as in Article 11c (in relation to the obligation of Member States regarding the transfer of records and certification processes of those organisations for which the Agency is the competent authority) and in Article 4 (1) — the obligation of Member States to adapt grandfathered pilot licences to the new format by a certain date.

The 'opt-out' is a form of transition measure applicable to Member States. Opt-out provisions allowed Member States to decide not to implement an EU regulation or certain provisions thereof for a certain period of time, delaying the date of application of the new regulation (or certain provisions thereof) within that Member State. For example, the opt-out provisions contained in the Aircrew and Air Ops regulations required the Member State to notify the European Commission and EASA of the 'opt-out', describing the reasons for such derogation and the programme for the phasing out of the opt-out and achieving full implementation of the common requirements.

Read more on opt-in and opt-out.

What is the difference between 'entry into force' and 'date of applicability' in the Cover Regulations?

Many Commission Regulations adopted in EASA domains contain two different dates, usually under the heading “entry into force”. The example below is from Regulation (EU) No 965/2012 on air operations:

Article 10

Entry into force

1. This Regulation shall enter into force on the third day following that of its publication in the Official Journal of the European Union.

It shall apply from 28 October 2012.

The entry into force of an EU regulation represents the date when the regulation has legal existence in the EU legal order and in the national legal order of each Member State.

It is common practice that the regulation enters into force 20 days after its publication in the Official Journal of the EU. That is the case when the legislator simply uses the expression “This Regulation enters into force on the 20th day after its publication in the Official Journal of the European Union.” Shorter periods are also used, as was the case in the example above.

Sometimes the date of entry into force is also the date of applicability of a regulation, meaning that from the date when it enters into force, the regulation is also applicable; it can be fully invoked by its addressees and is fully enforceable.

However, due to the complexity of the domains that are regulated, a period of time may be needed between the date the regulation enters into force, i.e. it legally exists, and the date it can actually be applied, i.e. the date when it is enforceable and the legal rights and obligations can be effectively exercised.

This period of time (vacatio legis) is deliberately introduced for Member States, competent authorities, operators, organisations, licence holders and any other addressees or beneficiaries of the regulations to prepare their systems, processes, procedures, documentation, etc. for compliance with the new rules.

Vacatio legis is also a period given for the addressees of the regulation to adjust to the upcoming rights and obligations and take the necessary measures to benefit from the legal effects of the regulation, namely for the purposes of mutual recognition of certificates and approvals in the aviation internal market.

In those cases, it is common practice of the legislator to establish two different dates under the article on entry into force. One date establishes the legal existence of the act (entry into force); the second date establishes the date when it becomes applicable (applicability).

The date of applicability therefore represents the date from which the regulation can produce rights and obligations on the addressees and can be directly enforced towards the courts, administrations, national governments, etc. This means that before the date of applicability, obligations or privileges can neither be exercised nor enforced.

The same understanding is shared by the Legal Service of the Commission, which has also clarified in EASA Committee that the privileges provided for in a regulation can only be exercised as of the applicability date chosen by the legislator. Persons subject to the relevant regulation (including national aviation authorities) may prepare themselves for such an effective date (adapting their procedures and practices), but can neither enjoy the privileges nor enforce the obligations.

Legal consequences

This means that Member States cannot start delivering authorisations, approvals, certificates, etc. issued in accordance with the new regulations and at the same time producing all the legal effects of the regulation from the date of entry into force of the regulation, but only from the date of its applicability. However, during the gap period existing between the date of entry into force and the date of applicability, Member States and competent authorities can prepare the process towards the issuance of such authorisations, approvals, and any other certificates in accordance with the new provisions.

In addition, during the period of vacatio legis, an option that Member States and competent authorities can consider, in order to avoid issuing certificates on the last day before the date of applicability, is to issue the new certificates in accordance with the new regulation while clearly indicating in those certificates that they are only valid as of a certain date that would coincide with the date of applicability of the regulation on the basis of which those certificates are issued. This means that those new certificates may be issued, but are not yet effective and cannot be mutually recognised among Member States until the common date of applicability established by the regulation. Until they become effective, licence holders, organisations and operators should still retain and use the certificates already issued under the previous regime. Competent authorities are only obliged to accept the new certificates once the regulation has become applicable.

When will the new rules on air operations be applicable?

Reference: Regulation (EU) No 965/2012 on Air Operations and its amendments

Regulation (EU) No 965/2012 entered into force on 28 October 2012.

Article 10 of the Air OPS Regulation includes an opt-out provision allowing Member States to postpone the applicability of Annexes I to V until 28 October 2014. This means that entire Annexes and/or specific parts of the Annexes will not be applicable if a Member States chooses to opt-out. The Agency has published an overview of the opt-out period applied by Member States here.

The amendments to the Regulation (EU) No 965/2012 have different applicability dates:

- Commission Regulation (EU) No 800/2013 on non-commercial operation became applicable on 25 August 2013 and the opt-out period is 3 years.

- Commission Regulation (EU) No 71/2014 on operational suitability data was published on 27 January 2014; it entered into force on the twentieth day following that of its publication and must be applied not later than 18 December 2017 or two years after the approval of the operational suitability data, whichever is the latest.

- Commission Regulation (EU) No 83/2014 on flight and duty time limitations and rest requirements was published on 29 January 2014, entered into force on the twentieth day following that of its publication and shall apply from 18 February 2016 and from 17 Feb 2017 for ORO.FTL.205(e).

Once the Implementing Rules have been adopted, it is still possible that transition measures defer their applicability to a later date. Therefore, the exact date of applicability of each requirement will depend on the transition measures adopted by the European Commission. Until the date the new Implementing Rules apply, Member States' national rules and EU-OPS remain in force.

What is the comitology procedure?

Please refer to the information provided by the European Commission on comitology.

Why can't I find EU-OPS on the EASA website?

Reference: Regulation (EU) No 965/2012 on Air Operations, associated Decisions (AMC/GM)

EU-OPS was the basis for the creation of Regulation (EU) No 965/2012 on air operations, which is the currently applicable regulation in the field of air operations with aeroplanes and helicopters.

EU-OPS is published in the Official Journal of the EU as Regulation (EC) No 859/2008 of 20 August 2008 amending Council Regulation (EEC) No 3922/91 as regards common technical requirements and administrative procedures applicable to commercial transportation by aeroplane.

What is the status of 'Implementing Rules', 'Acceptable Means of Compliance' (AMC), ‘Certification Specifications’ (CS), Alternative Means of Compliance (AltMOC), 'Guidance Material' (GM), ‘Special Conditions’ and 'Frequently Asked Questions'(FAQ)?

Implementing rules (IRs) are binding in their entirety and used to specify a high and uniform level of safety and uniform conformity and compliance. They detail how to comply with the essential requirements of the Basic Regulation and regulate the subject matters included in its scope. The IRs are adopted by the European Commission in the form of Regulations. EU law is directly applicable (full part of Member States' legal order).

Detailed implementation aspects are included as Certification Specifications (CS) or Acceptable Means of Compliance (AMC).

Acceptable Means of Compliance (AMC) are non-binding. The AMC serves as a means by which the requirements contained in the Basic Regulation and the IRs can be met. The AMC illustrate a means, but not the only means, by which a requirement of an implementing rule can be met. Satisfactory demonstration of compliance using a published AMC shall provide for presumption of compliance with the related requirement; it is a way to facilitate certification tasks for the applicant and the competent authority. However, NAAs and organisations may decide to show compliance with the requirements using other means. Both NAAs and the organisations may propose alternative means of compliance (AltMoCs). ‘Alternative Means of Compliance’ are those that propose an alternative to an existing AMC. Those AltMoC proposals must be accompanied by evidence of their ability to meet the intent of the IR. Use of an existing AMC gives the user the benefit of compliance with the IR.

Read more on the difference between AMC and AltMoC.

Certification Specifications (CS) are non-binding technical standards adopted by EASA to meet the essential requirements of the Basic Regulation. CSs are used to establish the certification basis (CB) as described below. Should an aerodrome operator not meet the recommendation of the CS, they may propose an Equivalent Level of Safety (ELOS) that demonstrates how they meet the intent of the CS. As part of an agreed CB, the CS become binding on an individual basis to the applicant.

Special Conditions (SC) are non-binding special detailed technical specifications determined by the NAA for an aerodrome if the certification specifications established by EASA are not adequate or are inappropriate to ensure conformity of the aerodrome with the essential requirements of Annex VII to the Basic Regulation. Such inadequacy or inappropriateness may be due to:

- the design features of the aerodrome; or

- where experience in the operation of that or other aerodromes, having similar design features, has shown that safety may be compromised.

SCs, like CSs, become binding on an individual basis to the applicant as part of an agreed CB.

Guidance Material (GM) is non-binding explanatory and interpretation material on how to achieve the requirements contained in the Basic Regulation, the IRs, the AMCs and the CSs. It contains information, including examples, to assist the user in the correct understanding and application of the Basic Regulation, its IRs, AMCs and the CSs.

Frequently Asked Questions: FAQs are published on the EASA website and cover a wide range of material. Although the information contained in the FAQs is a summary of existing law or procedures, it may contain the results of a more complex interpretation of IR or other rules of law. In such cases there is always an internal quality consultation within the Agency prior to the publication of the FAQ on the website. The EASA FAQs are necessary to share information and enable to get a common understanding.

The FAQs are not additional GM.

Does Reg. (EU) No 965/2012 on air operations also apply to non-commercial operations?

References: Regulation (EU) No 965/2012 on air operations as amended by Regulation (EU) No 800/2013; Reg. (EC) No 216/2008

Yes, non-commercial operations with aeroplanes and helicopters are covered by Reg. (EU) No 965/2012 on air operations. The applicable rules are determined by the complexity of the aircraft being used: Annex VI (Part–NCC) applies to non-commercial operations with complex motor-powered aircraft) and Annex VII (Part–NCO) applies to non-commercial operations with other-than-complex motor-powered aircraft.

The definition of complex motor-powered aircraft is found in Article 3 of Reg. (EC) No 216/2008. Pursuant to Article 140(2)(a) of Regulation (EU) 2018/1139 (the New Basic Regulation), ‘complex motor-powered aircraft’ shall still be understood as a reference to point (j) of Article 3 of Regulation (EC) No 216/2008. This is a transitional provision until not later than 12 September 2023, when the implementing rules adopted on the basis of Regulations (EC) No 216/2008 and (EC) No 552/2004 shall be adapted to this Regulation. The definition is as follows:

“complex motor-powered aircraft' shall mean:

(i) an aeroplane:

- with a maximum certificated take-off mass exceeding 5 700 kg, or

- certificated for a maximum passenger seating configuration of more than nineteen, or

- certificated for operation with a minimum crew of at least two pilots, or

- equipped with (a) turbojet engine(s) or more than one turboprop engine, or

(ii) a helicopter certificated:

- for a maximum take-off mass exceeding 3 175 kg, or

- for a maximum passenger seating configuration of more than nine, or

- for operation with a minimum crew of at least two pilots,

or

(iii) a tilt rotor aircraft”.

The definition for 'commercial operation' is in Article 2 of Regulation (EU) No 965/2012:

“(1)(d) 'commercial operation' means any operation of an aircraft, in return for remuneration or other valuable consideration, which is available to the public or, when not made available to the public, which is performed under a contract between an operator and customer, where the latter has no control over the operator”.

Training flights fall under either Part-NCC or Part-NCO, depending on the complexity of the aircraft used for the non-commercial operations.

In addition, Part-SPA applies to any operation requiring a specific approval (e.g. low visibility operations, transport of dangerous goods, performance-based navigation and more).

Finally, Annexes II (Part-ARO) and III (Part-ORO) contain the authority requirements and respectively the organisation requirements. Annex III applies to operators of complex motor-powered aircraft, both commercial and non-commercial.

I am not familiar with the Air ops rules’ structure. Which parts apply to which operators?

Reference: Regulation (EU) No 965/2012 on Air Operations and the associated Decisions

This is determined by the nature of your flight, and in the case of non-commercial operations, by the type of aircraft used. The following diagram indicates under which requirements your flight should be operating.

|

Commercial operations |

Commercial air transport (CAT) operations |

Technical rules: Part-CAT |

|

|

Operator rules: Part-ORO |

|||

|

Specialised operations (aerial work) |

Technical rules: Part-SPO |

||

|

Operator rules: Part-ORO |

|||

|

Non-commercial operations |

Non-commercial operations other than SPO |

With CMPA: |

Technical rules: Part-NCC |

|

With Ot-CMPA: |

Technical rules: Part-NCO |

||

|

Specialised operations |

With CMPA: |

Technical rules: Part-SPO |

|

|

With Ot-CMPA |

Technical rules: Part-NCO |

||

Part-SPA (specific approvals) applies to all types of operations, as the case may be.

CMPA = complex motor-powered aircraft

Ot-CMPA = other-than complex motor-powered aircraft

How can I find out where a rule from EU-OPS / JAR-OPS 3 has been transposed in the new Regulation (EU) 965/2012 on Air Operations and its amendments, as well as its associated EASA Decisions, and if any changes have been introduced?

Reference: Regulation (EU) No 965/2012 on Air Operations, associated Decisions (AMC/GM)

The Agency has published a cross-reference table to assist industry in transitioning to the new rules. This table contains detailed information on the transposition of EU-OPS / JAR-OPS 3 provisions (both Section 1 and Section 2 - for aeroplanes, TGL 44) into the new Implementing Rules (IR), Acceptable Means of Compliance (AMC) and Guidance Material (GM):

- new rule reference and rule title;

- old rule reference and rule title;

- indication of any differences to EU-OPS / JAR-OPS 3 provisions by stating “No change”, “Amended”, “New” or “Not transposed”; and

- short description of the differences, if any, between the old and new rules.

With this cross-reference table one can analyse in detail where and how the old provisions have been transposed into the new regulatory framework.

Which operational requirements (EU/EASA Parts) apply to flight activities carried out by an aircraft designer or aircraft manufacturer?

Reference: Regulation (EU) No 965/2012 on Air Operations

At the present stage no EU operational requirements exist for flights related to design and production activities (“manufacturer flights”). Instead these flights are regulated under national law. This is laid down in Paragraph 3 of Article 6 of Regulation (EU) No 965/2012 as follows:

“By way of derogation from Article 5 of this Regulation and without prejudice to point (b) of Article 18(2) of Regulation (EU) 2018/1139 and to Subpart P of Annex I to Commission Regulation (EU) No 748/2012 concerning the permit to fly, the following flights shall continue to be operated under the requirements specified in the national law of the Member State in which the operator has its principal place of business, or, where the operator has no principal place of business, the place where the operator is established or resides:

(a) flights related to the introduction or modification of aeroplane or helicopter types conducted by design or production organisations within the scope of their privileges; (…)”

Where can I find a list of alternative means of compliance that have been adopted by operators and NAAs in the EU?

In the Information on Alternative Means of Compliance notified to the Agency page there is a list with all the AltMoCs adopted by the Member States.

Definitions

What are critical phases of flight?

Reference: Regulation (EU) No 965/2012, Annex I Definitions

Annex I (Definitions) of the Regulation (EU) 965/2012 on air operations contains definitions for critical phases of flight for aeroplanes and helicopters:

“'Critical phases of flight' in the case of aeroplanes means the take-off run, the take-off flight path, the final approach, the missed approach, the landing, including the landing roll, and any other phases of flight as determined by the pilot-in-command or commander.

'Critical phases of flight' in the case of helicopters means taxiing, hovering, take-off, final approach, missed approach, the landing and any other phases of flight as determined by the pilot-in-command or commander.”

As one can see from these definitions, for helicopters taxiing is defined as a critical phase of flight, while for aeroplanes it is not. Rules for activities considered acceptable during critical phases of flight are provided in the Regulation (EU) No 965/2012 on air operations – in Annex III (Part-ORO), Annex IV (Part-CAT), Annex VI (Part-NCC), Annex VII (Part-NCO) and Annex VIII (Part-SPO). Basically, these implementing rules require crew members during critical phases of flight:

- to be seated at his/her assigned station; and

- not to perform any activities other than those required for the safe operation of the aircraft

What are 'Sterile Flight Deck Procedures'?

Reference: Regulation (EU) No 965/2012 on Air Operations, Annex I (Definitions) and Annex III (Part-ORO)

The term 'Sterile Flight Deck' is used to describe any period of time when the flight crew members shall not be disturbed e.g. by cabin crew, except for matters critical to the safe operation of the aircraft and/or the safety of the occupants. In addition, during these periods of time the flight crew members should focus on their essential operational activities without being disturbed by non-flight related matters, i.e. flight crew members should avoid non-essential conversations, should not make non-safety related announcements towards the passengers, etc.

Sterile flight deck procedures are meant to increase the flight crew members' attention to their essential operational activities when their focused alert is needed, i.e. during critical phases of flight (take-off, landing, etc.), during taxiing and below 10 000 feet (except for cruise flight).

The sterile flight deck procedures were published in Regulation (EU) 2015/140 as an amending regulation to (EU) No 965/2012 on air operations. EASA published the associated AMC and GM with ED Decision 2015/005/R.

What is the difference between 'commercial operation' and 'commercial air transport (CAT) operation'?

Reference: Regulation (EC) No 216/2008, Regulation (EU) No 965/2012

The term 'commercial operation' is now defined in Article 2 of Regulation (EU) No 965/2012 as follows (previously in Reg. (EC) No 216/2008):

“'Commercial operation' means any operation of an aircraft, in return for remuneration or other valuable consideration, which is available to the public or, when not made available to the public, which is performed under a contract between an operator and a customer, where the latter has no control over the operator.”

The term 'commercial air transport (CAT) operation' is defined in Article 3 of Regulation (EU) 2018/1139 as follows:

“'Commercial air transport' means an aircraft operation to transport passengers, cargo or mail for remuneration or other valuable consideration.”

The two definitions make it clear that 'commercial operations' include 'CAT operations'. Specialised operations (SPO) are another type of commercial operations. They are also defined in Article 2 of Reg. (EU) No 965/2012.

Part-ARO

AMC2 ARO.GEN.305(c) Oversight programme (c) stipulates that audits should include at least one on-site audit within each oversight planning cycle. What is meant by an 'on-site audit' in this sentence? Could it be so that every audit undertaken by an NAA could be performed while sitting in the NAA's office and reviewing operator's documents and procedures and only one of those audits should be undertaken in a way that NAA inspectors actually visit an operator on-site?

Reference: Regulation (EU) No 965/2012 on Air Operations, Annex II (Part ARO, ARO.GEN and ARO.RAMP)

There is no further guidance on how many on-site audits should actually be performed. This decision depends on the confidence of the authority in the operator, on results of past certification and/or oversight activities required by ARO.GEN and ARO.RAMP and on the assessment of associated risks. The number of on-site audits is therefore part of the oversight responsibility of the authority.

How do the provisions on wet-leasing articulate with Regulation (EU) No 452/2014 on Third Country Operators (TCO)?

Reference: Regulation (EU) No 965/2012, Annex III (Part ORO)

The TCO authorisation issued by the Agency is no substitute for requirements regarding wet-lease agreements between EU and third country operators that are contained in Part ORO of Regulation (EU) No 965/2012 on Air Operations. For wet-lease agreements, the TCO operator must demonstrate equivalence to EU safety requirements. Before entering into a wet-lease agreement, the EU operator should demonstrate to the authority that (1) the TCO has a valid AOC, (2) that safety standards of the TCO regarding continuing airworthiness and air operations are equivalent to the EU continuing airworthiness requirements of Reg. (EU) No 1321/2014 and (3) the aircraft has a standard Certificate of Airworthiness (CofA) issued in accordance with ICAO Annex 8.

Must the competent authority check and approve the content of the operator's Safety Management Manual?

Reference: Regulation (EU) No 965/2012 on Air Operations, Annex II (Part ARO), Annex III (Part ORO)

As stated in ORO.AOC.100, an operator has to submit, as part of its application for an AOC, a description of its management system, including the organisational structure, which constitutes its safety management manual, whose content is described in AMC1 and AMC2 to ORO.GEN.200(a)(5).

The Competent Authority has to check the content of the operator's Safety Management Manual (SMM) as mentioned in ARO.GEN.310(a) and in the corresponding AMC to ARO.GEN.310.

Information on the content of the operator's Safety Management Manual (SMM), which can be part of the Operations Manual or included in a separate manual, can be found in AMC1 and AMC2 to ORO.GEN.200(a)(5). It should be noted that the SMM is not required to be approved according to ORO.GEN.200(a)(5) and the related AMCs. Nevertheless, changes affecting the operator's management system are required to be approved (ORO.GEN.130 + GM1) and these changes would have to be reflected in the operator's manual dealing with Safety management.

How do the provisions on code-sharing articulate with the Regulation applying to Third Country Operators (Part TCO)?

Reference: Regulation (EU) No 965/2012, Annex III (Part-ORO)

Regarding code-sharing, Regulation (EU) No 965/2012 on air operations requires from the EU Operator, who wishes to enter into a code-sharing agreement with a third country operator (TCO), compliance with the requirements of Annex III to Regulation (EU) No 965/2012. This means the TCO as a code-share partner will undergo comprehensive audits for the initial verification of compliance and continuous compliance with the applicable ICAO standards [AMC1 ORO.AOC.115(a)(1)]. These audits can be performed either by the EU operator itself or a third party provider. The AMC (AMC2 ORO.AOC.115(b)) refers to the possibility of using industry standards. The audit will focus on the operational, management and control systems of the TCO (see AMC1 ORO.AOC.115(a)(1)).

Continuous compliance of the code-sharing TCO with the applicable ICAO standards will be performed on the basis of a code-share audit programme (see AMC1 ORO.AOC.115(b)).

This means that the audit and verification requirements contained in Part-ORO of Regulation 965/2012 cannot be substituted by a TCO authorisation issued by the Agency. For code-share, an EU operator must, in addition to the TCO authorisation, audit and monitor the TCO.

Part-ORO

ORO.GEN

ORO.GEN.110 (a): “The operator is responsible for the operation of the aircraft in accordance with Annex IV to Regulation (EC) No 216/2008”. Is this requirement met when an Operator follows the Implementing Rules (965/2012)?

Reference: Regulation (EU) No 965/2012 on Air Operations, Annex III (Part-ORO)

The Essential Requirements (ER) are as applicable as the implementing rules.

The operators are responsible for checking that they comply with all the Essential Requirements contained in Annex IV of the Regulation (EC) 216/2008.

Some implementing rules make a direct reference to the Essential Requirements. This is the case when an ER is not further developed in the implementing rules.

What are the responsibilities of the AOC holder required to implement a management system in accordance with ORO.GEN.200 in regards to continuing airworthiness management and contracted maintenance?

Reference: Regulation (EU) No 965/2012 on Air Operations, Annex III (Part-ORO); Regulation (EU) No 1321/2014 on continuing airworthiness, Part-M

1. Continuing airworthiness management

The EU licensed air carrier hereafter referred to as ‘the operator’, needs to consider both the relevant Part-ORO rules that will become fully applicable on 29 October 2014 and the applicable Part-M requirements. For these operators, the Part-M Subpart-G approval is an integral part of the AOC (as defined in Part-M, M.A.201(h)).

The Part-M requirements have not yet been amended to align with the management system framework adopted for air operations. However the operator should ‘scrutinise’ all its activities under its hazard identification and risk management processes, including the continuing airworthiness activities. It is the operator’s responsibility to ensure that hazards entailed by any continuing airworthiness management task are subject to the applicable hazard identification procedures and that related risks are managed as part of the operator’s management system procedures.

If the operator’s continuing airworthiness activities do not comply with the new management system requirements adopted with Part-ORO the competent authority may not raise any finding in reference to Part-M Subpart G, but may do so under Part-ORO should it consider that the operator’s safety risk management process does not sufficiently capture those risks stemming from the continuing airworthiness management activities that may impact the safety of operations. The integration of safety management across all activities will lead to increased efficiency and effectiveness in hazard identification and risk management as compared to a system where activities are being dealt with in isolation through separate management systems. This will improve the assessment of risks identified and ensure better allocation of resources to address these risks, by eliminating conflicting or duplicating procedures and objectives.

When it comes to assessing compliance with Part-ORO competent authorities should acknowledge that implementing effective safety risk management capabilities for all activities subject to the approval will take time and therefore a balanced approach for checking compliance is needed to enable a smooth transition towards the new management system requirements.

Considering the benefits of taking a holistic, integrated approach to management system for effective safety management, competent authorities should also not mandate the implementation of separate management systems for the different approvals of the same organisation. Competent authorities should instead focus on assessing whether the management system implemented is adequate as regards the size, nature and complexity of the activities it is deemed to cover.

2. Maintenance

The issue is slightly different in the area of contracted maintenance: As the Part-145 requirements have not yet been amended to align with the management system framework adopted for air operations, the maintenance organisation may not have established a management system to effectively identify maintenance specific hazards and manage related risks. However, the operator would still need to consider such hazards and risks entailed by contracted maintenance, as it would do for any other contracted activity that has an impact on aviation safety, under its own management system. Once Part-145 organisations will have implemented the new management system requirements including safety risk management, the operator will be able to establish an interface with the hazard identification and risk management processes of the maintenance organisation and consider the contracted organisation’s capability to properly address maintenance specific hazards and risks for their own safety risk management.

This FAQ addresses the case of EU licensed air carriers, meaning operators holding both and AOC in accordance with Regulation (EU) No. 965/2013 and an operating licence in accordance with Regulation (EC) No 1008/2008

Is there a difference between safety risk management (SRM) and SMS?

Reference: Regulation (EU) No 965/2012 on Air Operations, ICAO Annex 19

ICAO defines SMS as “a systematic approach to managing safety, including the necessary organisational structures, accountabilities, policies and procedures.”

While SRM is an essential element within a management system for safety, it is not the only element required. To be effective, SRM needs a structured approach and an organisational framework with clearly defined policies, safety responsibilities and accountabilities. Such framework is essential to facilitate and encourage hazard identification, ensure a structured & consistent approach to risk assessment, as well as for allowing informed decisions to be made at the right organisational level, e.g. in relation to risk acceptability or different risk mitigation options. For example, the organisation needs to put in place policies, procedures and mechanisms for internal safety reporting and then maintain the conditions for allowing such reporting to take place.

Also, in order to ensure that the organisation is continually managing its risks it needs to monitor how well it performs, both in terms of effectiveness of risk controls implemented and effective compliance with applicable requirements. This is part of safety assurance, which is another component of an SMS as per ICAO Annex 19.

Additionally the organisation has to train their staff to fulfil their duties, including those related to any safety management task and to properly communicate on any safety relevant issue.

All this should lead to ensuring a systematic approach to SRM and help fostering the necessary ‘culture’ within the organisation to enable careful management and sound understanding of risk, including in day-to-day activities.

In conclusion, SRM, while being a core element of any management system for safety, should not be singled out as the only element required to implement such system.

See also the FAQ on SMS versus management system above.

Why do the EASA Air Operations rules use the term ‘management system’ (ORO.GEN.200) and not ‘safety management system’ (SMS), like in ICAO Annex 19? Is there a difference between the two concepts?

Reference: Regulation (EU) No 965/2012 on Air Operations, Annex III (Part-ORO)

In the area of SMS the Agency promotes consolidated general requirements for an organisation’s management system. The starting point for drafting the ‘first extension’ rules are the essential requirements attached in the annexes to the Basic Regulation (Regulation (EU) 2018/1139) and these refer to ‘management system’, cf. the essential requirements for air operations (Annex V, point 8.1 (c)):

“(…) the aircraft operator must implement and maintain a management system to ensure compliance with the essential requirements set out in this Annex, manage safety risks and aim for continuous improvement of this system;” (…)

The underlying concept is that for managing safety it is essential to take a holistic approach and to implement the new safety risk management (SRM) related processes while making use of and integrating these into the already existing management system (e.g. quality system as per JAR-OPS/ EU-OPS). For example, the internal audit process (compliance monitoring) is kept as an essential element of the management system, while ICAO Annex 19 is not that clear about it.

Hence, organisations should be encouraged to integrate the new SRM elements into their existing system and articulate these with the way the organisation is managed, addressing every facet of management, as any organisational change and any decision (even in areas such as Finance, Human Resources) will need to be assessed for their impact on safety. Such integrated approach to management is much more efficient for monitoring compliance, managing risks and maximising opportunities.

Finally, it is not required that organisations adapt their terminology to that used in Part-ORO: Should they wish to refer to SMS, QMS or SQMS etc., this is possible as long as they can demonstrate that all requirements are met. In the same vein, they can still use the title ‘quality manager’, although the rules refer to compliance monitoring manager.

If an operator is considered complex , may a person hold the position as a Safety Manager and at the same time be one (or more) of the nominated persons as described in ORO.GEN.210(b), taken into account the size and complexity of the operator?

There is no guidance indicating that the safety manager may not be a nominated person in the organisational set up of a complex operator.

However, when assessing the organisational set-up of a complex operator, please consider also GM1 ORO.GEN.200(a)(1) point (b): “Regardless of the organisational set-up it is important that the safety manager remains the unique focal point as regards the development, administration and maintenance of the operator’s safety management system”.

In summary, the role of the safety manager is not addressed at the level of implementing rules. The acceptable means of compliance describe the functions of the safety manager in complex operators. The guidance material emphasises on the importance of having a unique focal point for the operator’s safety management system.

It is for the operator to determine if the combination of the safety manager function with that of a nominated person allows to fulfil the management functions of the nominated persons post associated with the scale and scope of the operation. It is then for the competent authority to assess if such organisational set-up corresponds to the size of the operator and the nature and complexity of its activities, taking into account the hazards and associated risks inherent in these activities.

For the assessment of the appropriateness of the organisational set-up, the competent authority should also be satisfied that the operator complies with ORO.GEN.210(c) “The operator shall have sufficient qualified personnel for the planned tasks and activities to be performed in accordance with the applicable requirements.”

I am looking for the acceptance of post holders, particularly the Safety manager. In the AMC we agreed on the functions of the Safety manager, but did we agree on his or her acceptance?

Reference: Regulation (EU) No 965/2012 on Air Operations, Annex II (Part ARO, ARO.GEN.310, ARO.GEN.330), Annex III (Part ORO, ORO.GEN.130)

Part ORO does not mention anymore the notion of acceptance/acceptability of nominated persons. This is now replaced by the notion of changes requiring prior approval or changes not requiring prior approval.

During the initial certification process, nominations of personnel in general are considered to be part of the verification of compliance performed by the competent authority and therefore covered by the issuance of the AOC.

Regarding changes to certified organisation, the notion of changes requiring prior approval/changes not requiring prior approval applies and therefore, a formal approval of certain change is required. Guidance is provided through GM1 ORO.GEN.130(a) and GM3 ORO.GEN.130(c). Likewise, upon initial certification, the competent authority may agree with the organisation on a more specific scope of changes that do not require prior approval, on the basis of ARO.GEN.310(c), and within the limits of the applicable requirements. Items not required to get a prior approval are managed by the organisation based on a procedure approved by the competent authority for the management of such changes. In any case, these changes have to be notified to the competent authority which will verify compliance with the applicable requirements (cf. ORO.GEN.130(c) and ARO.GEN.330(c)).

Regarding the specific case of the safety manager, it should be noted that there is no requirement for a safety manager at an implementing rule level. The nomination of a safety manager is one means to comply with the IR objective. Therefore, a change in safety manager is not listed in the GMs to ORO.GEN.130: A change in safety manager is not considered a change requiring a prior approval from the competent authority, unless, the accountable manager fulfils the role of safety manager, in which case a change would obviously require prior approval.

The above references are those to Regulation (EU) No 965/2012; the same provisions are included in Regulation (EU) No 290/2012 (ARA/ORA).

Regarding ORO.GEN.200, could a commercial operator of complex motor powered aircraft, such as the Cessna Citation Bravo that operates within Europe and with no SPAs, be considered non-complex?

Reference: Regulation (EU) No 965/2012 on Air Operations, Annex III (Part ORO)

As defined in AMC1 ORO.GEN.200(b) the criterion in terms of full-time equivalents (FTEs) is the first one to be checked. This relates not only to the required organisational capability to implement and maintain a management system in line with Part ORO, but also to the fact that the larger the organisation gets, the more complex its procedures, communication and feedback channels will be, hence the need for robust processes related to hazard identification, safety risk management, performance measurement etc. For an organisation up to 20 FTEs, it is important to assess the 'risk profile' of the organisation in relation to the way it operates and this may justify the need for robust management processes for safety. The AMC defines the most relevant ones. The extent of contracting, the number, complexity and diversity of aircraft operated and type of operations (CAT, commercial, local, standard routes, hostile environment etc.) are all to be considered. It is important to note that the complexity criteria are included in an AMC to Part ORO and this makes a strong point as to the responsibility of the operator to make the assessment and justify the option chosen (complex or non-complex management system) to the satisfaction of the competent authority. If the option is to implement the provisions applicable to complex organisations, having details of management system implementation included in the form of AMCs to ORO.GEN.200, the operator may apply for an alternative means of compliance should it consider any of the elements of these AMCs inadequate for its specific type of organisation and operations.

ORO.MLR

How should an operator use external material in relation with its operations manual (OM)?

Reference: Regulation (EU) No 965/2012 on Air Operations, Annex III (Part ORO)

AMC1 ORO.MLR.100 states that when the operator chooses to use material from other sources, either this material is copied or the OM should contain a reference to the appropriate section of this material.

In any case, this material from another source is considered to be part of the OM and therefore should meet all the general requirements applicable to the OM. It includes:

- (c) of ORO.MLR.100, which states that the OM shall be kept up-to-date;

- (d) of ORO.MLR.100, which states that the personnel shall have easy access to the portions of the OM relevant for their duties;

- (c)(3) of AMC1 ORO.MLR.100, which states that the content and amendment status of the manual is controlled and clearly indicated;

- (d)(3) of AMC1 ORO.MLR.100, which states that the OM should include a description of the amendment process which specifies the method by which the personnel are advised of the changes.

Regulation (EU) No 965/2012 does not define any specific way to achieve this; therefore it is left to the operator to identify the best way to achieve these objectives. It is then the responsibility of the operator’s competent authority during the initial certification process/evaluation of change process to determine if the solution chosen by the operator allows meeting these requirements.

ORO.FTL

Status of the EASA FAQ: What is the legal status of the EASA FAQ? My own understanding of this document is that it has no legal standing at all, insofar as it is neither an Implementing Rule (IR), Acceptable Means of Compliance (AMC), Alternative Means of Compliance (AltMoc) nor even Guidance Material (GM).

EASA is not the competent authority to interpret EU Law. The responsibility to interpret EU Law rests with the judicial system, and ultimately with the European Court of Justice. Therefore any information included in these FAQs shall be considered as EASA's understanding on a specific matter, and cannot be considered in any way as legally binding.

The answers provided represent EASA’s technical opinion and also indicate the manner how EASA is evaluating, as part of its standardisation continuous monitoring activities, the application by national competent authorities of the respective regulatory provisions.

In the margins of its future rulemaking activities, EASA will consider the opportunity to include some of these FAQ in Subpart FTL as GM.

Applicability of FTL requirements of Regulation (EU) No 965/2012: Why should we comply with the FTL requirements of Regulation (EU) No 965/2012, since we have a policy in our company that says otherwise?

Regulation (EU) No 965/2012, including Subpart FTL, is mandatory in all Member States (MS).

This means that an operator cannot maintain a ‘policy’ it has had before the date of application of Subpart FTL of Regulation (EU) No 965/2012, unless the policy has been found compliant with that Regulation.

The competent authority of the operator is responsible for checking for compliance and for taking enforcement measure when a non-compliance is found.

Applicability of Regulation (EU) No 965/2012: What is the meaning of "applicable national flight time limitation legislation" in Article 8 (4) of Regulation 965/2012?

Reference: Regulation (EU) No 965/2012 as amended by Regulation (EU) No 83/2014

Topic: Applicability of Regulation (EU) No 965/2012

Article 8(4) of Regulation (EU) No 965/2012 stipulates that specialised operators continue to comply with applicable national flight time limitation legislation until EU implementing rules are adopted and apply.

‘Applicable national flight time limitation legislation’ is understood to mean the national law of the Member State in which the operator has its principal place of business, or, where the operator has no principal place of business, the place where the operator is established or resides.

Collective Labour Agreements (CLA) - Regulation (EU) No 83/2014: Our company has a Collective Labour Agreement (CLA) and an approved IFTSS. Both contain rules about FPD’s, DP’s and rostering. Which one is leading?

Recital (4) of Regulation (EU) No 83/2014 stipulates that: ‘The provisions of this Regulation do not preclude and should be without prejudice to more protective national social legislation and CLA concerning working conditions and health and safety at work.’

This means that more protective measures concerning FDP, DP and rostering, agreed under a CLA, are ‘leading’.

Applicability of Subpart FTL (see also ORO.AOC.125): Does Subpart FTL apply in relation to non-revenue flights (ferry flights)?

Any flight conducted by an AOC holder falls under Subpart FTL with the exception of:

- some non-revenue flights such as: non-commercial, test, training, delivery, ferry and demonstration flights;

- air taxi, single pilot and emergency medical services operations by aeroplane; and

- CAT operations by helicopter, including HEMS.

However, aircraft positioning conducted by an AOC holder, immediately before or after a CAT sector counts as FDP and sector.

Acclimatisation ORO.FTL.105(1): How should we determine the state of crew member acclimatisation in complex rotations?

Acclimatised crew members

A crew member is considered to be acclimatised to the time zone of the reference time for the first 48 hours.

In the following example there are 4 departure places: A, B, C and D and the crew member is in a known state of acclimatisation all the time.

- between A and B there is a 2-hour time difference

- between A and C – a 4 hour-time difference

- between A and D – a 6-hour time difference

Day 1: The crew member starts acclimatised at A and finishes at B. The reference time is the local time at A, because the crew member is acclimatised at A and reports at A. The time difference between A and B is 2 hours. That means that after resting at B, the crew will be considered acclimatised at B.

Day 2: The crew member reports at B acclimatised to the local time at B for an FDP to C. At C the crew member has a rest period and becomes acclimatised to C. He/she has now covered 4-hour time difference, but in 2 days.

Day 3: The crew member reports at C acclimatised to the local time at C for an FDP to D. At D the crew member has a rest period and becomes acclimatised to D. He/she has now covered 6-hour time difference.

Day 4: The crew member reports again considered to be acclimatised at D. The local time at D is the reference time. The FDP between D and A covers 6-hour time difference. Crossing 6-hour time difference in one day (one FDP) induces time zone de-synchronisation. If the rotation finishes at A, the rest requirements in CS FTL.1.235 (b)(3)(i) are applicable.

Unknown state of acclimatisation

After the first 48 hours of the rotation have elapsed, the crew member is considered to be in an unknown state of acclimatisation.

The crew member only becomes acclimatised to the destination time zone, if he/she remains in that destination time zone for the time established in the table in ORO.FTL.105 (1).

During that time the crew member may have the rest in accordance with CS FTL.1.235(b)(3) and/or take other duties that end in different time zones than the first arrival destination, until he/she becomes acclimatised in accordance with the values in the table in ORO.FTL.105(1). In the case of duties to different time zones, the state of acclimatisation should be determined in accordance with GM1 ORO.FTL.105(1) (d)(3).

Where the rotation continues with duties to/from subsequent destinations, the greatest time difference from the reference time should be used for the purpose of rest in accordance with CS FTL.1.235(b)(3)(i).

Time elapsed since reporting (h) in the tables ORO.FTL.105 (1) and CS FTL.1.235 (b)(3)(i) is the time that runs from first reporting at home base to the reporting at destination and includes the FDP from home base to destination plus layover time.

Accommodation ORO.FTL.105 (3): Can the airport crew lounge be considered as “accommodation” for the purpose of standby or split duty? Can a hotel room for several crew members of the same gender be considered as “accommodation” for the purpose of standby and split duty?

As long as an airport crew lounge or a shared hotel room fulfils all criteria of ORO.FTL.105 (3) it could be used as accommodation.

Disruptive schedule ORO.FTL.105(8): Which criteria should be applied to determine a duty as disruptive if there is a time zone difference between the reporting point and the place where the duty finishes?

The criteria to be applied is the reference time e.g. the local time (LT) where the crew member reported for duty.

Example with “Late type” of Disruptive schedule:

LT in A = LT in B + 1 hour.

Day 1: The crew member starts the FDP acclimatised to A. He/she reports at 15:00 (LT-A) and finishes FDP in B at 23:30 (LT-B). It is a ‘Late finish’ because he/she is acclimatised to A, and FDP finishes at 00:30 (LT-A).

Rest in B. After resting in B, which is within two hours’ time difference from A, the crew member gets acclimatised to B.

Day 2: The crew member reports in B at 15:00 (LT-B) and finishes FDP in A at 00:30 (LT-A). It is not a late finish, because he/she is acclimatised to B, and the FDP finishes at 23:30 (LT-B).

Definition of duty and duty period, ORO.FTL.105 (10), ORO FTL 105 (11): Must the time for self-preparation (e.g. preparing for the checks associated with initial or recurrent training) be entered in the schedule of the crew members and recorded?

The time needed for self-preparation, is not a duty and is not recorded.

Single day free of duty ORO FTL 105 (23): A ‘single day free of duty’ consists of one day and two local nights. Does the last day of several consecutive days free of duty need to contain at least one day and two nights?

Whenever one of the local days prescribed by Clause 9, Directive No 2000/79/EC, is assigned as a single day, it must contain two local nights. Whenever consecutive local days are assigned, the last day may not contain a local night. However, from a fatigue management perspective, planning the last day to end at midnight, reduces the restorative effect of that last day to a minimum. Rising before midnight to report at 00:01 on the last day could generate sleep debt.

The term ‘single day free of duty’ has been included in Regulation No 965/2012 in order to enable the implementation of Directive No 2000/79/EC, in particular its Clause 9:

‘Clause 9

Without prejudice to Clause 3, mobile staff in civil aviation shall be given days free of all duty and standby, which are notified in advance, as follows:

(a) at least seven local days in each calendar month, which may include any rest periods required by law; and

(b) at least 96 local days in each calendar year, which may include any rest periods required by law.’

Clause 9 above employs the term ‘local day’ i.e. a period of 24 hours finishing at 00:00 LT. At the same time, a ‘single day free of duty’ is a period of one day, including two local nights, that may finish between 06:00 and 08:00 LT, depending on the local night start and end times.

Sector ORO.FTL.105 (24), (see also ORO.FTL.205 (f)(6)): In an abnormal or emergency situation a take-off might not be executed meaning that a sector was not completed. Such situation is likely to increase flight crew workload and fatigue. How could this be mitigated?

In such cases, in order to mitigate the increased workload and fatigue, the commander has the possibility to exercise commander’s discretion and decide on reducing the maximum daily FDP or increasing the minimum rest period.

ORO.FTL.205 (f)(6) requires operators to implement a non-punitive process for the use of commander’s discretion.

Also, if as a result of such situation a flight crew member feels unfit dues to fatigue, he/she may discontinue his duties on the aircraft for the day.

Regulation (EU) No 376/2014 on the reporting, analysis and follow-up of occurrences in civil aviation, requires the ability for crew members to report fatigue.

Changes to a published roster: Is it possible to make changes to a published roster?

Yes, provided that the changes do not breach the limitations of the operator’s Individual Flight Time Specification Scheme (IFTSS).

All changes must be notified to the crew member before the pre-flight rest period commences so that the crew member is able to plan adequate rest as required by ORO.FTL.110 (a).

In support of this requirement the minimum period of time for notification of changes should be established by the operator and available in the Operations manual

Change of FDP after reporting: Can a rostered FDP be changed (re-planned) after crew members have reported?

There are no specific provisions and conditions for such changes except in unforeseen circumstances, where, on the day, a Commander may use the provisions of Commander’s Discretion:

- to continue with an FDP which exceeds the maximum FDP that the crew will operate or reduces the minimum rest period, or

- to reduce the actual FDP and/or increase the rest period, in case of unforeseen circumstances which could lead to severe fatigue.

The operator may not plan or change an FDP at any time such that it exceeds the maximum applicable FDP.

FTL rules build upon the predictability of rosters so that crews can plan and achieve adequate rest (ORO.FTL.110 (a) and (g)). Operators are expected to plan sufficient capacity, at their operating bases, to deal with disruptions normally expected in daily operations using the specific FTL provisions (e.g. stand-by, reserve). Therefore, FDP changes after reporting should be an infrequent event as such changes can create roster instability and may generate fatigue. An aircrew member remains at all times under the responsibilities set out in CAT.GEN.MPA.100 (c)(5) to report unfit to fly, if s/he suspects fatigue which may endanger flight safety.

If changes to planned duties are to be made on the day of operation, all applicable limits apply: in particular the limits established pursuant to ORO.FTL. 205(b), (d), (e) or ORO.FTL.220. If a duty has not been planned with an operator’s extension under ORO.FTL. 205(d), it cannot be changed into a duty with such extension on the day of operation.

In addition, the operator must ensure that the impact on forward duties and days off, and importantly on cumulative limits, is accounted for.

EASA recommends that changes made on the day of operation to duties and FDP’s are monitored through appropriate performance indicators that operators use to demonstrate they fulfil all the required elements within ORO.FTL.110. The 33% exceedance threshold on the max FDP as set out in ORO.FTL.110 (j) may not always be adequate to capture negative trends.

EASA also recommends that appropriate performance indicators for FDP changes after reporting be part of the operator’s approved IFTSS to ensure that any resulting fatigue hazards are properly identified and mitigated.

Roster publication, (see also AMC1 ORO.FTL.110(a) and ORO.GEN.120): Are airline operators allowed to publish monthly rosters in less than 14 days in advance?

According to AMC1 ORO.FTL.110 (a), rosters should be published 14 days in advance.

This requirement is an acceptable means of compliance (AMC). The AMC is one example of how operators could demonstrate compliance with this rule.

In accordance with ORO.GEN.120, an operator may use an alternative means of compliance.

It is therefore possible to use an alternative means of compliance (AltMoc) for the publication of rosters, provided the operator has demonstrated that the requirements of ORO.FTL.110 (a) are met.

An alternative means of compliance requires prior approval from the competent authority.

The competent authority must notify all approved alternative means of compliance to EASA.

Reporting times ORO.FTL.110(c), (see also ORO.FTL.205(c)): Can the pre-flight reporting time for non-augmented flight crew members reporting for the same FDP be different?

No. The pre-flight reporting time for all non-augmented flight crew members reporting for the same FDP is the same.

The minimum reporting times, which have been defined by the operator in the Operations manual for different types of aircraft, operations and airport conditions, shall always apply to all flight crew.

Reporting time for the same FDP may be different between flight crew and cabin crew in accordance with ORO.FTL.205(c).

Operational robustness ORO.FTL.110(j): How should operational robustness be assessed?

The operator is required to have measures in place to protect the integrity of schedules and of individual duty patterns.

The operator must monitor for exceedances to the planned flight duty periods and if the planned flight duty periods in a schedule are being exceeded more than 33% during a scheduled seasonal period, change a schedule and/or crew arrangements.

Operational robustness should be measured through performance indicators to determine if the planning is realistic and the rosters are stable.

The operator may measure the cases where a rostered crew pairing for a duty period is achieved within the planned duration of that duty period.

Performance indicators may also be established to measure the following:

- difference between planned and actual flight hours;

- difference between planned and actual duty hours;

- difference between planned and actual number of days off;

- number of unscheduled overnights;

- number of roster changes per scheduled seasonal period;

- use of commander’s discretion;

- changes of schedule carried out after published roster

With regard to operator’s responsibilities, in particular operational robustness of rosters, we also recommend guidance material to ORO.FTL.110 developed by UK CAA.

Flying activities outside an AOC (see also ORO.FC.100): How will activities as an instructor or an examiner performed by an operating crew member in their free time be considered for the purpose of duty time and rest periods?

The purpose of Subpart-FTL is to ensure that crew members in commercial air transport operations are able to operate with an adequate level of alertness. It does not regulate the activities performed by crew members in their free time.

Nonetheless, it is the responsibility of crew members to make optimal use of the rest periods and to be properly rested so they will not perform duties when unfit due to fatigue.

A crew member in commercial air transport operations may be required to report to the operator his/her professional flying activities outside the commercial air transport operation to allow the operator to discharge its responsibilities (ORO.FTL.110) appropriately.

An operator should establish its policy with regard to crew members conducting these kinds of activities.

Deviation from the applicable CS ORO.FTL.125 (c) (see also ARO.OPS.235): What does a deviation from the applicable CS mean or derogation from an implementing rule?

The flight time specification schemes of an individual operator (IFTSS) may differ from the applicable CS / IRs under strict conditions.

The operator has a number of steps to follow before implementing a deviation/derogation.

Additionally, the competent authority has a number of steps to follow before approving a deviating/derogating IFTSS.

All the steps are described in this Evaluation Form (link) developed by EASA to facilitate NAAs and operators in this process.

Flight time specification scheme for air taxi operations, (see also Articles 2 (6) and 8(2) of Regulation (EU) no 965/2012): An air taxi operator has both an aeroplane with less than 19 seats and one aeroplane with more than 20 seats. What FTL regulation shall the crew who is flying both types follow?

The operator implements Subpart ORO.FTL for its operations with aeroplanes of 20 seats or more.

For air taxi operations with aeroplanes of 19 seats or less, the operator complies with EU OPS, Subpart Q.

However, the aim of the requirements is to ensure that crew members are able to operate at a satisfactory level of alertness. Fatigue accrued during an operation in one fleet might impact on the performance of a crew member when conducting a following flight in the other fleet.

Therefore, from a fatigue management perspective, it makes sense to apply a common FTL scheme under Subpart ORO.FTL consistently to pilots in such operations.

Approval of Individual Flight Time Specification Schemes (IFTSS), (see also ARO.OPS.235):

May a competent authority give ONE approval for an individual flight specification scheme to be used by three different operators with three AOCs?

No. Each operator needs its own approved individual flight time specification scheme.

Unknown state of acclimatisation GM1 ORO.FTL.205(b)(1): If the crew member is in an unknown state of acclimatisation, what is the reference time?

In that case, there is no reference time. For crew members in an unknown state of acclimatisation Table 3 in ORO.FTL.205 (b)(2) or Table 4 ibidem applies. These Tables do not contain any reference time.

Unknown state of acclimatisation ORO.FTL.205(b)(3): What are the daily FDP limits when crew members are in an unknown state of acclimatisation under fatigue risk management (FRM)?

Table 4 in ORO.FTL.205 (b)(3) establishes the limits of the maximum daily FDP when crew members are in unknown state of acclimatisation and the operator has implemented FRM.

Mixing FDPs extended without in-flight rest and FDP’s extended due to in-flight rest ORO.FTL.205 (d) ORO.FTL.205 (e): Is it possible to roster two extended FDPs without in-flight rest and one extended FDP with in-flight rest in 7 consecutive days?

Yes. The limit of two extensions of up to 1 hour in 7 consecutive days specified in ORO.FTL.205 (d) (1) only applies to the use of extensions without in-flight rest by an individual crew member.

Planned FDP extensions ORO.FTL.205(d): Must planned extensions be included in the operator’s roster?

Published duty rosters may or may not include extended FDPs.

However, FDPs extended in accordance with ORO.FTL.205 (d) must be planned and notified to crew members in advance i.e. allowing each crew member to plan adequate rest.

The time limit for notification of a planned extended FDP to an individual crew member need to be established by the operator in line with ORO.FTL.110 and specified in the OM-A.

Planned FDP extensions ORO.FTL.205(d) (see also ORO.FTL.105(1)): Can a crew member acclimatised to the local time of the departure time zone (‘B’ state), but not acclimatised to the local time where he/she starts the next duty (‘D’ state), be assigned a planned extended flight?

While it may be legal to roster an extended FDP (no in-flight rest) to a crew member who is not acclimatised to the local time where the actual duty starts, the actual operational environment may be such that it would be very fatiguing for a particular crew member to perform that FDP.

Although operations on an extended FDP are possible under ORO FTL.1.205(d), the operator still needs to comply with the fatigue management obligations stemming from ORO.FTL.110 and especially to ensure that the crew members are sufficiently rested to operate.

Commander’s discretion ORO.FTL.205(f): Do we need to use Commander’s discretion if actual FDP is going to last more than planned but less than the maximum daily FDP allowed?

No. If the actual FDP is less than the maximum allowed, commander’s discretion is not needed.

Commander’s discretion ORO.FTL.205(f): When should commander’s discretion be used?

Commander’s discretion may be used to modify the limits on the maximum daily FDP (basic or with extension due to in-flight rest), duty and rest periods in the case of unforeseen circumstances in flight operations beyond the operator’s control, which start at or after the reporting time.

Considering the ICAO definition of ‘unexpected conditions’, unforeseen circumstances in flight operations for the purpose of ORO.FTL.205(f) are events that could not reasonably have been predicted and accommodated, such as adverse weather, equipment malfunction or air traffic delay, which may result in necessary on-the-day operational adjustments.

Commanders cannot be expected to exercise discretion without an understanding of the events that constitute unforeseen circumstances. It is therefore necessary that they receive appropriate training on the use of commander’s discretion along with how to recognize the symptoms of fatigue and to evaluate the risks associated with their own mental and physical state and that of the whole crew.

Operators should ensure that sufficient margins are included in schedule design so that commanders are not expected to exercise discretion as a matter of routine

Commander’s discretion ORO.FTL.205(f), (see also ORO.FTL.205 (d)): 1. What is the maximum FDP extension allowed under commander’s discretion? 2. How would commander’s discretion apply when the FDP of a non-augmented crew has already been extended in accordance with ORO.FTL.205 (d))?

1. Up to 2 hours for two pilot crew and up to 3 hours for augmented crew.

2. For a two pilot extended FDP operation, the use of commander’s discretion is always based on the maximum daily FDP table ORO.FTL.205 (b) (1).

For example, when 1 hour has already been added to the maximum daily FDP in accordance with ORO.FTL.205 (d), then only 1 hour is left for commander’s discretion.

Commander’s discretion ORO.FTL.205(f): Referring to commander’s discretion, do I need to consider the reporting time and number of sectors?

Yes. The commander needs to consider the actual number of sectors that the crew members will complete as this may be different from the plan. This FDP calculation would be based on the time the crew member actually reported.

Conversion/line checks Post flight duty ORO.FTL.210: How should briefings and debriefings during conversion/line checks be accounted for?

In accordance with the definition of duty, conversion/line training is duty.

Any duty (including the briefing and debriefing for training purposes) after reporting for a duty that includes a sector or a series of sectors until the aircraft finally comes to rest and the engines are shut down, at the end of the last sector on which the crew member acts as an operating crew member, is considered flight duty period.

Post flight duties, on the other hand (including debriefings also for training purposes), are considered as duty period.

Post-flight duty AMC1 ORO.FTL.210(c): What should the operator do if the actual post flight duty time is longer than the established time in the OM?

The operator needs to implement a monitoring system to ensure that the minimum time period for post-flight duties is adequate since rest or shortened rest could potentially impact fatigue.

The commander or a cabin crew member should inform the operator where the post-flight duties have taken longer than planned and this is then accounted for in duty and rest periods.

Positioning for purposes other than operating ORO.FTL.215 (b): How should time spent to travel from the place of rest or home base to a simulator (when outside the base) be taken into account?

The time spent to travel from a place of rest or home base to a simulator, at the request of the operator, counts as a duty period.

Any transfer of a non-operating crew member from one place to the other at the request of the operator is called positioning and is counted as a duty period.

Travel from a crew member’s private place of rest to the reporting point at home base and vice versa, and local transfers from a place of rest to the commencement of duty and vice versa are travelling, but not positioning, and so not counted as duty period.

Positioning ORO.FTL.215: Does positioning begin when the crew member arrives at the airport/train station or when the aeroplane/train leaves?

Positioning begins after reporting at the designated reporting point.

The operator should publish reporting times taking into account the time necessary for completing the travelling procedures depending on the mode of transportation (e.g. registration of passengers and baggage, security checks, etc.).

First example: Crewmember 1 is required to position from A to B on the commercial flight of an airline other than the airline which Crewmember 1 is flying for. This commercial flight is departing at 10:00, but airport A is an international airport and the time necessary for passenger and baggage registration and security checks is 2h before departure time. In this case, the positioning begins 2h before departure time.

Second example: Crewmember 2 is required to position from A to B on a high speed train. This train is departing at 10:00 and the time necessary for passenger and baggage registration and security checks is 15 minutes before departure time. In this case, the positioning begins 15min before departure time.

Positioning ORO.FTL.215: Shall a positioning between active sectors count as a sector for a pilot or cabin crew?

No, any positioning within an FDP does not count for the sector calculation of the FDP limit but counts towards the FDP.

Split duty ORO.FTL. 220: Is it possible to have more than one split duty within one FDP?

No. ORO.FTL.220 provides for a break on the ground which implies a single break on the ground, for the purpose of extending the basic daily FDP.