Originally published in the Norwegian CAA safety letter, article and online guide of October 2025, and republished by invitation.

GPS signal lost - What now?

We’ve grown used to having GPS as a navigation aid on every flight. For VFR pilots, GPS and digital moving map displays have increased situational awareness and reduced workload in the cockpit. But what happens if the GPS signal suddenly disappears or provides incorrect information? This is not just a theoretical exercise. In some areas, GNSS interference has become a daily occurrence. Pilots flying in Northern Norway experience GPS interference almost every day on certain routes.

The threat of losing the GPS signal in flight is real, and it’s important to know how to detect the problem and manage it safely. In this article, we look at what can cause loss of GPS signal during VFR flight, how you’ll notice that the signal is gone, and which actions you can take.

Most pilots say “GPS,” but the correct generic term is “GNSS” (Global Navigation Satellite System).

Possible causes of GPS signal loss

There are several reasons why GPS can fail in the air, broadly divided into unintentional and intentional interference:

Unintentional interference

These occur without anyone deliberately trying to disrupt the signals. A typical example is technical failure of equipment. Either in the aircraft or on the ground. Even a faulty antenna or nearby electronics can emit interference that drowns out the GPS signal. There have for instance been cases where a broken antenna on an excavator disrupted GPS reception on a construction site, forcing work to stop. Another source can be strong solar activity (solar storms) that degrades or interferes with signals from the satellites. Terrain and obstacles can also have an effect. Flying in a narrow valley or near high mountains can lead to poor satellite coverage if signals are blocked, although this is usually less of a problem in the air than on the ground. Finally, the GPS receiver in the aircraft itself can fail (hardware or software), causing the navigation equipment to malfunction.

Intentional interference

This happens when someone deliberately manipulates GPS/GNSS signals. The most common is jamming, where a ground transmitter overwhelms the weak GPS signals with noise so the receiver cannot obtain a position. A more advanced phenomenon is spoofing, in which a transmitter sends false GPS signals, making the receiver indicate it is somewhere else than correct position. In military contexts there is also meaconing (repeating/delaying signals), but for civil aviation jamming and spoofing are the most relevant terms. GNSS interference of these types has increased markedly in recent years, particularly following conflicts. Since 2022 there has been a noticeable rise in jamming and spoofing globally, especially around conflict zones and sensitive regions such as the Middle East, the Black Sea, the Baltic Sea, the Mediterranean, and the Arctic. In Europe, the Baltic states and Scandinavia have reported frequent GPS interferences after the outbreak of war in Ukraine. In fact, jamming around the Baltic Sea has increased so much over the last year that it affects large areas from Poland through the Baltic states to the coasts of Sweden and Finland. This includes lower altitudes where VFR is commonly flown.

In Norway’s northern areas (Finnmark), jamming has become an “undesired normal” according to the Norwegian Communications Authority (Nkom). Such deliberate interference can stem from military activity (e.g., Russia jamming GNSS during exercises or warfare) or from use of illegal equipment that that is available to the public. Regardless of cause, the result is that GPS-based signals either are unavailable (jamming) or become unreliable (spoofing).

How do you notice that the GPS signal is gone?

The first step in managing a GPS failure is detecting that it has happened. Fortunately, most modern GPS units and navigation apps will alert you when the signal is lost, but this varies with the equipment used.

Alerts or error messages

Many receivers give a clear indication. Anything from a simple “GPS signal lost” text on the screen to an oral warning tone. Both in glass cockpits and GPS units, you might see messages like “Loss of GPS integrity” or similar. Such messages mean the device no longer trusts the GPS position and that the data may be wrong.

Moving maps freezes up or position is missing

If you fly with a tablet/EFB or GPS-based map, you will typically see the position symbol stop updating. The map “freezes,” or the position marker turns red/is crossed out. This indicates that sufficient satellite reception has been lost. In the case of jamming, the positions indicator will simply disappear. The device receives no signals at all. Under spoofing, however, you may still have a seemingly valid signal, but the information doesn’t make any sense.

Inconsistencies

You may find that the GPS position shows you somewhere unexpected, that groundspeed is odd compared to indicated airspeed or time/clock jumps abnormally. For example, sudden position deviations or false terrain warnings when there is no real hazard. For a VFR pilot, it may look like the GPS indicates you’re drifting off your route or miles away from where you visually see where you are. That’s when your gut feeling should kick in: trust your own senses and other instruments if GPS data seem suspicious.

Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS) Outages and Alterations | EASA

Many navigation apps update a digital operational flight log that calculates when you will be over waypoints and your ETA at destination. With incorrect time and position, this plan will no longer be valid.

Warnings and related system dropouts

In aircraft with integrated navigation systems (e.g., glass cockpits or older IFR GPS with RAIM monitoring), you will typically get a warning indicating that GPS is no longer being used for navigation. If you’re flying with an autopilot or flight director coupled to GPS, the system may disconnect or enter reversion mode. In some cases, related systems can also be affected. For example, the Terrain Awareness system (TAWS/EGPWS) may not function when the GPS signal is gone. One crew experienced jamming. The system began to fail because of lacking position and altitude information and the pilots received alerts in cockpit.

Stay vigilant. If you detect that the GPS has dropped out or is showing dubious data, acknowledge the situation quickly and switch to alternative navigation methods. Don’t be fooled by a GPS that appears to be working when there are clear indications something is wrong. Several pilots have ended up off course because they ignored signs that the GPS was unreliable. Be especially alert if you’re entering areas known for GNSS interference (e.g., the far north). A sudden GPS failure may be due to jamming, not your device.

What can you do when the GPS signal fails?

If the the problem occurs, act calmly. Here you will find some steps to handle the situation:

Aviate

As always, fly the airplane first. Don’t fixate on the GPS problem immediately. Maintain steady heading and altitude and make sure you avoid terrain and traffic. If you’re near controlled or complex airspace, take the necessary steps to remain clear until you’ve regained full control of navigation.

Navigate using alternative methods

Once the aircraft is stable, maintain visual pilotage using ground references. Get out your paper chart (or digital backup) and visually identify your position using terrain, towns, roads, water, etc.

If you are flying IFR, use classic dead-reckoning: set heading with the magnetic compass, use the clock, and estimate distances. It remains important to rely on conventional navaids based on VOR, NDB, and DME. On approach, the ILS is likely correct even with a discrepancy towards GNSS.

During VFR flights you should always know where you are based on visual references. Perhaps there is a distinctive landmark nearby? If the aircraft has conventional radio-navigation instruments like VOR, NDB, or DME on board, use them. Tune a VOR station and determine the radial, or use the ADF if available, to obtain a cross-bearing and fix your position.

EASA recommends that pilots verify the aircraft’s position using non-GNSS navaids if jamming occurs. The same applies if spoofing is suspected; actively cross-check position against ground-based navaids and information from ATS.

Use available backups

If you have an extra GPS unit or another independent source, check whether it works. Some pilots fly with a handheld GPS as a backup, or a tablet app with its own GPS receiver. Be aware that with wide-area GNSS interference (e.g., region-wide jamming), all GPS-based devices will likely lose signal at the same time. But if the cause was a failure in the aircraft’s installed receiver or antenna, a handheld unit may still have coverage. A tablet with its own GPS or a smartphone can provide temporary navigation information. Remember mobile devices often have weaker antennas and may also be affected by local interference.

Transponder and ADS-B

Many modern transponders with ADS-B Out also transmit GPS-based position. When GPS is lost, ADS-B position will be affected, but it’s worth knowing that ATS can often see that “something is not adding up” if they suddenly lose your position. The main point: Use available resources in the cockpit. Normally ATS can use the transponder to pinpoint your position, using radar rather than ADS-B.

Try simple troubleshooting (time and situation permitting)

If you suspect your own GPS device is the problem (e.g., the unit froze or the software crashed) and you have capacity, you can attempt a quick restart of the receiver or navigation app. Note that rebooting takes time. GPS typically must “boot” and reacquire satellites, which may take from seconds to a couple of minutes. Do this only if you have sufficient capacity (or an autopilot) and not if it distracts from actually navigating. In many cases a restart won’t help if the cause is jamming. The signals will be blocked. If you have flown some distance away from a possible jammer, signals may suddenly return. But don’t base your safety on this. Plan for the GPS to be unavailable for the rest of the flight.

Inform and communicate as needed

If losing GPS means you are no longer sure of your position, or you are near controlled airspace/approach areas, it’s wise to talk to a friendly voice. Contact ATS on the radio and report the situation. A simple way is to declare “lost position” and ask for navigational assistance. ATC can give you a radar vector or a bearing to the nearest aerodrome. ATS may already be aware that jamming is ongoing in the area (via reports from other aircraft or NOTAM). In any case they will assist a pilot who asks for help. Remember, it’s not embarrassing to report navigation problems. Safety comes first. For VFR pilots in uncontrolled airspace, it may be appropriate to contact ATS to ask if they have reports of GPS problems and to request traffic information.

Emergency?

If you truly become disoriented and lack references (for example, over solid cloud at night), consider declaring an emergency (MAYDAY/PAN) to receive priority assistance. In daytime VMC this will rarely be necessary. There are usually enough visual references to sort it out without a full distress call, but it can still be smart to inform ATS.

Maintain situational awareness and make good decisions

Once the acute phase is handled and you have a plan for continuing without GPS, assess the rest of the flight. Should you continue to destination without GPS or would it be wiser to discontinue? This depends on several factors such as terrain, weather, and how comfortable you are with traditional navigation on the planned route. If the route ahead crosses barren areas with few reference points, consider turning toward more familiar terrain or an aerodrome where you can re-orient. If you’re flying far offshore or across tundra with few cues, navigation is extra demanding. As a VFR pilot, you usually have options: you can orbit above or near known landmarks, or land at a suitable aerodrome.

Report interference

After the flight and especially if you suspect that loss of GPS support was due to jamming or spoofing, consider filing a report. The Civil Aviation Authority (CAA Norway) wants to know about GNSS interference that affects safety. Note the time, position, and altitude where you experienced the problem and send a report. EASA also encourages pilots to report GNSS interference, particularly spoofing cases that can provide new insight into safety challenges.

Number of reported cases as of August 2025 for Norway (figure)

In Norway, Nkom also has a role in tracking down illegal jammers. They can attempt to eliminate the source if it is on Norwegian territory. Even if the GPS was only out for a few minutes and you handled it fine, your feedback is valuable for mapping the scope of the problem.

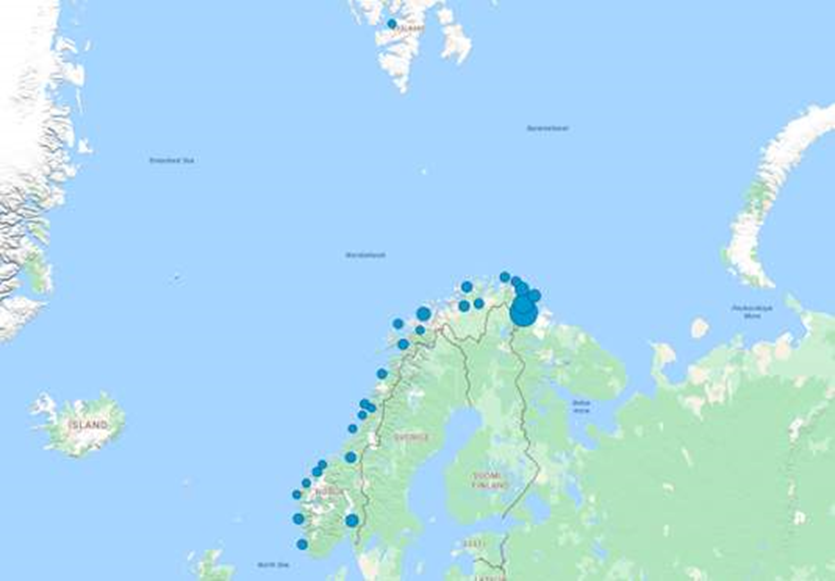

Positions of reported cases in Norway related to aerodromes (figure)

Note that if the GPS outage had no safety consequences, it may not be mandatory to report, but a voluntary report can also be very valuable.

Summary

Fly the aircraft first, navigate using alternatives, communicate if necessary, and keep a cool head. A GPS outage is manageable- Especially in VFR conditions, as long as you haven’t forgotten the basics of navigation.

Be prepared - Threat and Error Management (TEM)

Most importantly, be prepared before a potential GPS failure occurs. In the TEM philosophy, loss of navigation equipment is considered a threat. An external factor that can increase risk if you’re not aware of it. Good TEM practice is about identifying such threats in advance and thinking through what can go wrong and what you will do if it happens.

Tips to be prepared

Plan the route with “old methods” as well

Even if you intend to use GPS, you should plan using charts and lay out the route with visual waypoints. Note landmarks along the way such as rivers, roads, towns, and mountains that you can use to verify your position enroute. Calculate headings, distances, and times between these points as if you had no GPS. Then you have a backup navigation plan ready. If GPS fails, you can simply continue navigating according to your plan using chart and clock, instead of improvising from scratch. This is classic defensive flying, always have a “plan B.”

Carry charts and necessary equipment

It sounds obvious, but many pilots today fly without paper charts readily available in the cockpit. Make sure you have current VFR charts for the areas you’ll fly over and place them so they can be reached quickly (ideally pre-folded). Keep a compass and a stopwatch handy. The point is to avoid being left empty-handed. Steinar Thomsen at the Norwegian Space Agency points out that society in general should take precautions in case GNSS signals disappear. By keeping a road atlas in the car to alternative ways of obtaining correct time.

Check NOTAMs

Stay updated on whether GPS interference is notified in your area or along your route. Military jamming tests occur from time to time and should be published via NOTAM. For example, a major jamming test is conducted annually at Andøya in Northern Norway, where GNSS is deliberately interfered with within a defined area. Such tests are announced, and as a pilot you should be aware so you can plan around them (either by avoiding the area or being prepared to navigate without GPS there). Check GPS system status messages (e.g., RAIM).

Practice the “GPS fails” scenario

Include GPS outage in your self-training. This can be as simple as asking an instructor or flying partner to simulate a GPS failure on one of your training flights by covering the GPS device or turning it off. This may reveal any gaps in knowledge and preparation while you’re still in a controlled training situation. EASA recommends that flight crews be trained to recognize and respond to GNSS interference and that operators include such scenarios in their training programs. For private pilots, this is largely up to the individual.

In the end, it’s all about being prepared. TEM is essentially an extension of good old-fashioned airmanship. Being aware of what may challenge you and staying ahead. If, from the outset, you’ve acknowledged that “GPS may fail on this flight,” you will naturally keep a closer eye on the chart and terrain (so you notice immediately if GPS starts giving false information) and you’ll be better prepared to monitor the situation. Then a sudden GPS outage becomes more an irritation, rather than an emergency.

Summary

Loss of GPS signal during VFR flight is a manageable challenge as long as you are prepared and keep your head cool. The causes can range from innocent technical faults to deliberate jamming, but regardless of the cause, the key is to detect the problem quickly and use alternative navigation methods. Make sure you practice the scenario, have necessary backups available, and integrate this into your safety assessments. GPS has undoubtedly made everyday navigation easier and safer, but that’s precisely why we must actively counter a false sense of security that “GPS never fails.” Always be prepared and then you can confidently say: “I’ve got this - no problem!”

Sources

Norwegian Defence Research Establishment

Norwegian Space Agency

Norwegian Communication Authority

European Aviation Safety Agency

Civil Aviation Authority Norway

Please log in or sign up to comment.