The Threat and Error Management (TEM) model is a safety framework used to help anticipate, identify, assess and manage threats and errors associated with operations, flight environment, technical, human and organisational aspects. Every helicopter pilot should actively look for, spot, assess and manage threats and errors before and during the flight to avoid Undesired Aircraft States (UAS), and review performance after landing. This article is mainly based on the EHEST Leaflet HE 8 The Principles of Threat and Error Management for Helicopter Pilots, Instructors and Training Organisations, and uses various threat illustrations contained in previous videos, articles and leaflets.

Introduction

Origins, use in aviation and helicopter operations

The TEM model was developed in the mid-1990s by Professor Helmreich and a team of psychologists at the University of Texas. It originated from the Line Operations Safety Audit (LOSA) concept, a collaborative effort between the University of Texas Human Factors Research Project and Delta Airlines. The first full-scale TEM-based LOSA was conducted at Continental Airlines in 1996.

The TEM model is widely used in aviation to enhance safety by training flight crews to detect and manage threats, errors and Undesirable Aircraft States (UAS) effectively. It is integrated into Crew Respurce management (CRM) training, which emphasises teamwork, communication, decision-making, stress and fatigue management, and automation and flight path management. The TEM model is also used in instruction, safety audits and incident and accident investigation.

TEM proposes that threats, errors and UAS are everyday events that flight crews must manage to maintain safety. EASA Part FCL and ICAO require that Human Factors and TEM be introduced into all pilot training. In every flight phase, all pilots, from student through professional, shall demonstrate ‘attitudes and behaviours appropriate to safe conduct of flight, including recognising and managing potential threats and errors.’

By focusing on the interaction between human performance and the operational context, the TEM model provides a comprehensive approach to managing safety in aviation, including helicopter aviation.

In helicopter operations, the TEM model is particularly valuable due to the unique challenges and operational complexities involved. Helicopter pilots often face varied and dynamic environments, such as adverse weather conditions, confined landing zones, and low-altitude operations. The TEM model helps pilots anticipate, detect and manage threats, errors and Undesired Aircraft States (UAS, and keep margins of safety.

TEM model and definitions

Threat and error management is an operational concept applied to the conduct of a flight that is more than the traditional role of airmanship, as it provides for a structured and pro-active approach for pilots to use in identifying and managing threats and errors before the situation can deteriorates.

The TEM model features three basic components:

- Threats: External events or errors that increase operational complexity and must be managed to maintain safety margins. Threats can be anticipated, unexpected, or latent.

- Errors: Mistakes made by flight crews that can lead to undesired aircraft states if not managed properly.

- Undesired Aircraft States: Situations where the aircraft is in a condition that reduces safety margins, requiring immediate management to avoid unsafe outcomes.

Threats

Threats are defined as events or errors that occur beyond the influence of the flight crew, increase operational risk and must be managed to maintain the margins of safety.

During typical flight operations, flight crews have to manage various contextual threats. The TEM model considers three types of threats: anticipated, unanticipated and latent, which all have the potential to negatively affect flight operations and reduce margins of safety:

- Anticipated: Some threats can be anticipated by the flight crew and, while the lists below are not exhaustive, the major ones are:

- Thunderstorms, fog, haze, snow, wind shear, icing and other forecast bad weather

Source: EASA video

Rotorcraft Unintended IMC - Recovery in the Air (youtube.com)

- Night flight

- Congested airport or heliport

-

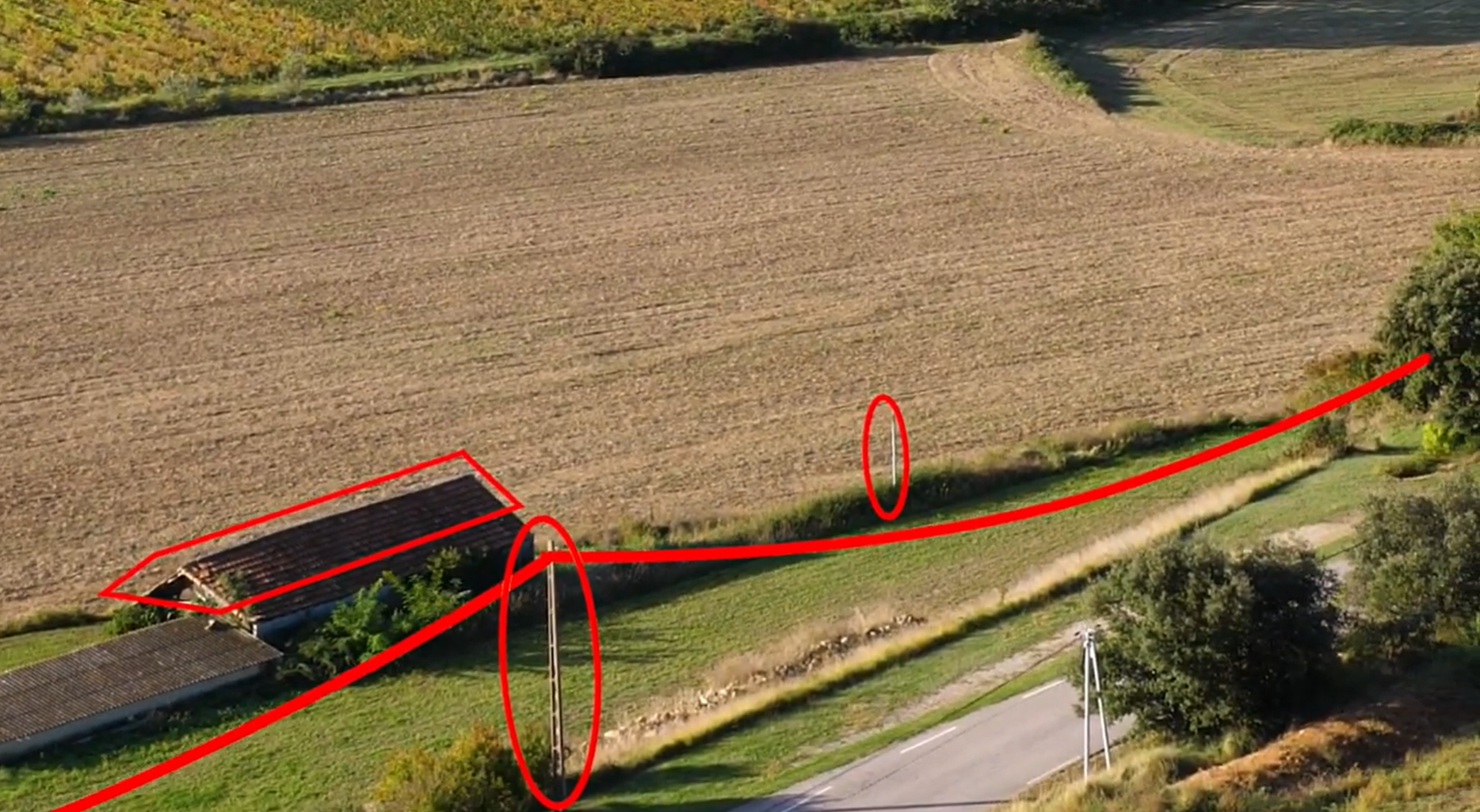

Obstacles and wires

Can you see the cables?

Picture credit: Michel Masson - Terrain

Source: EASA video Distraction and CFIT

- Complex ATC clearances

- Out of wind approaches and landings

- Sloping or congested landing areas, off airfield operations

- Air temperature or Density Altitude (DA) extremes

EHEST Leaflet HE 12 Helicopter Performance | EASA (europa.eu),

Power vs. True Airspeed chart

- Mass and balance

- Fuel capacity

- Forecast or known bird activity

- Unanticipated: Some threats can occur unexpectedly, suddenly and without warning. In this case, flight crews must apply competences and knowledge acquired through training and experience to manage them:

- In-flight aircraft malfunction

- Automation anomalies or disconnection

- Un-forecast weather, turbulence, windshear, sudden or worsening icing

- ATC re-routing, congestion, non-standard phraseology, navigation aid unserviceability, similar call signs

- Ground handling service changes

- Non-pre-identified wires or obstacles

Source: Video Appesi ad un filo (youtube.com),

Prevenire i rischi nel volo a bassa quota, Provincia Autonoma di Trento, Italy

- Traffic, unforeseen GA, Ultra-light, light aircraft and other activities

- Unmanned aircraft systems, also referred to as drones

- ACAS RA/TA

- Technical failures or degradations

- Fuel, oil or coolant leaks

-

Un-forecast bird activity

Source: EASA video

The Importance of Wearing Helmets when Flying a Helicopter

- Laser attacks

- Unforeseen sloping or congested landing areas, emergency landing

- Latent: Some threats may not be directly obvious to, or observable by, flight crews immersed in flight operations and may need to be uncovered by safety analysis. These are considered latent threats and may include organisational weaknesses and the psychological state of the pilot, such as:

- Company culture or culture changes

- Organisational changes, commercial and business pressures

- Operational pressures, delays

- Incorrect or incomplete documentation

- Equipment design issues

- Fatigue, rostering, chronic stress, medication, alcohol, drugs

- Cognitive biases, such as ‘get-there-itis’

- Unsafe attitudes

- Optical illusions, disorientation

- Overconfidence, complacency

-

Automation and flight path mis-mismanagement, over-reliance on automation, mode confusion, poor monitoring of automation or of flight parameters, head-down flying, using levels of automation not appropriate for the task, erosion of manual flying skills

Source: Leonardo Helicopters video

Automation and Flight Path Management (youtube.com)

- Lack of recency or proficiency.

Managing threats is essential to maintaining safety margins and avoiding UAS.

Errors

Errors are actions or inactions that lead to deviations from personal or organisational intentions or expectations. The TEM model focuses on errors made by the flight crew. Errors can also be made by other aviation personnel, passengers and other actors.

There are different types of errors:

• Slips and lapses are failures in the execution of the intended action. Slips are actions that do not go as planned, while lapses are memory failures. For example, pulling the mixture instead of the (intended) carburettor heat is a slip. Forgetting to apply the carburettor heat is a lapse.

• Mistakes are failures in intent or plan of action. Even if execution of the plan were correct, it would not have been possible to achieve the intended outcome because the intent or the plan are wrong. Intending to fly into bad weather to complete the flight as contracted is a (serious) mistake.

Managing errors contributes to avoiding UAS and maintaining margins of safety.

Note: Errors must be managed, but not all errors must be immediately corrected. Minor inconsequential errors can be left temporarily unattended, to allocate attention to higher priority or urgent actions. For instance, no need to correct radio frequency while landing or operating near to a cliff, power lines, other aircraft or obstacles, because this may distract from piloting the aircraft. Managing all errors indistinctly could lead to task saturation and so become counter-productive. Multiple minor errors can however combine and result in an unsafe situation. Managing errors requires assessing priorities, risks and consequences, and reassessing these as the situation evolves.

Undesired Aircraft States (UAS)

UAS are flight crew-induced aircraft position or speed deviations, due to misapplication of flight controls, or incorrect systems configuration, which reduce margins of safety.

UAS can also be environment-induced: turbulence, gusty winds and windshear, for instance.

UAS result from ineffective TEM or from unmanageable threats and errors.

UAS can compromise safety and can lead to incidents or accidents. Flight crews must manage UAS to prevent incidents and accidents.

The TEM model considers three categories of UAS: aircraft handling, ground navigation and incorrect aircraft configurations, which all have the potential to reducing margins of safety.

Examples are presented below:

- Aircraft handling:

- Vortex Ring State (VRS)

- Loss of Tail Rotor Effectiveness (LTE), also termed Unintended Yaw (UY)

Source: EASA video Unanticipated Yaw (youtube.com)

- Degraded Visual Environment (DVE)

-

Poor aircraft control (attitude)

Source: EHEST video Degraded Visual Environment and Loss of Control

- Vertical, lateral or speed deviations

- Unsuitable weather penetration

- Operation outside aircraft limitations

- Unstable approach

- Continued landing after unstable approach

- Under or overshooting the landing area, hard landing

- Ground navigation (heliport operations):

- Airspace infringement

- Proceeding towards wrong taxiway or runway

- Wrong taxiway, ramp, pad or hold spot

- Incorrect aircraft configuration:

- Systems

- Flight controls

- Automation

- Engine

- Mass and balance

Teaching TEM

Teaching threat management

Train pilots to actively look for and spot threats, for instance obstacles and cables in low altitude operations:

Source: EASA video Uncertified Helipad Landing (YouTube.com)

Tell pilots to use their eyes, ears, noise, touch and proprioception, and to pay attention to sounds, noises, fumes, vibrations, and anything abnormal or noticeable.

Threats and errors are a part of everyday aviation operations and must be managed through all the phases of flight:

- Pre-flight: Time should be spent identifying possible threats and errors associated with the flight in order to plan and develop countermeasures. For example, a possible threat in the circuit is other aircraft which could result in a mid-air collision. Possible errors that could lead to a UAS increasing the odds of mid-air collision are spending too much time with 'head down' not looking out, looking out in the wrong area, not scanning properly, or not listening out on the radio.

Countermeasures could be to develop a crew strategy for lookout, adopting a scan technique considering climbing, descending or turning, listening out on the RT for other traffic calling ATC for traffic information, etc.).

In addition, and equally valid in the context of recurrent training, a safety briefing prior to any flight should be given to raise the student’s safety awareness. Several safety issues can be discussed, referring to accidents and incidents in general or risks specifically related to the type of flights usually undertaken by the candidate.

TEM should be promoted as an effective mitigation. Practical application of TEM, illustrated with real-life examples should be discussed. There is no restriction on the subjects that could be covered. It may range from weather related issues to personal or passenger induced pressure, ‘press-on-itis’, etc. The material that can be used to support this briefing could come from accident & incident reports, mandatory or voluntary safety reporting, safety campaigns of different sources, and personal experience.

- In-flight: Brief on the planned procedures before takeoff and prior to commencing each significant flight sequence including anticipated threats and countermeasures covered in pre-flight briefings.

- Prioritise tasks and manage workload to avoid being overloaded (e.g., use checklists).

- Identify any UAS to the student and manage accordingly.

- Recover the helicopter to safe flight configuration safety margins before dealing with other problems.

Unanticipated threats are likely in flight. These threats are generally managed by applying competences and knowledge acquired through training and flight experience. Typically, practicing engine failure or simulated system failure are methods of training a pilot to manage unexpected threats. Knowledge and repetition prepare a trainee to manage such events should they occur for real in flight. Instructors should develop training scenarios, 'what if' questions or examples that will address the different categories of threats and thereby develop the trainee’s ability to detect and respond appropriately to threats.

During flight training, the instructor must identify unanticipated threats such as incorrect ATC instructions, traffic hazards or adverse weather and point them out to the trainee should they fail to identify them. Then it is important to question the trainee to see what steps they could take to mitigate the threats, ensuring that the action is completed in the time available.

A good technique to teach the student to recognise threats is to:

- Prompt: What is the threat?

- Question: How could it be mitigated?

- Direct: Do this.

- And if necessary, intervene: Take control.

- Post-flight: Reconsider what threats, errors and/or UAS were encountered during the flight. Ask the student how well they managed them and what they could do differently to improve the management of similar threats and errors on future flights, to assist with the development of improved TEM strategies.

Teaching error management

Acknowledging that errors will occur has changed the emphasis in aviation operations to error recognition and management, besides error prevention. Rather than just pointing out errors to the student as they occur, instructors should show the student how to minimise the chances of errors happening, and then if they do happen, detect them and implement strategies to manage them efficiently.

Instructors must afford the student the opportunity to recognise a committed error rather than intervening as soon as they see an error committed, they must wait (if time allows) to see if the error is identified by the trainee. If it is not, the instructor should then analyse why the error happened, why it was not identified and how to prevent future occurrences.

Rules, checklists, SOPs, briefings, action-control, hear-back & readback, and other professional practices contribute to preventing, catching and correcting errors. Whether a checklist is read (best option) or used from memory, they are provided to enhance safety by helping reduce errors.

Teaching UAS management

Unmanaged or mismanaged threats or errors may result in a UAS., and UAS in incidents or accidents.

Students should be trained to manage threats and errors before a UAS develops.

During flight training, instructors will be dealing with many UAS as trainees develop their flying competences. In this context, instructors have the dual role of practicing TEM by ensuring that UAS are managed and then teaching trainees to do the same.

Because students may not have the manipulative and cognitive skills of a qualified pilot, they will often not meet specified flight tolerances or procedures. Some typical examples are:

- Hover taxiing too fast

- Too fast or slow on final approach, or

- Inability to maintain altitude or heading during straight and level flight.

Although such examples would be classified as UAS when committed by a qualified pilot, they are not unusual events in flight training. The difference is that the instructor should be aware of the threats and errors and should not let an UAS develop into an incident or an accident.

A critical aspect that instructors must teach is switching from TEM to UAS management. During the error management phase, a pilot can become fixated on determining the cause of an error and forget to 'aviate, navigate, communicate' (in that order), which can result in a UAS.

References

EHEST Leaflet HE 8 The Principles of Threat and Error Management for Helicopter Pilots, Instructors and Training Organisations | EASA (europa.eu).

Helicopter Flight Instructor Guide - Issue 4.0 | EASA (europa.eu).

EHEST Leaflet HE 12 Helicopter Performance | EASA (europa.eu).

Safety behaviours: human factors for pilots 2nd edition Resource booklet 8 Threat and error. management (casa.gov.au).

Threat and error management (TEM) awareness material (aviation.govt.nz).

Threat and error management - Wikipedia.

Threat and Error Management (TEM) | SKYbrary Aviation Safety.

Threat and Error Management (TEM) in Flight Operations | SKYbrary Aviation Safety.

Helicopter Airmanship | EASA Community (europa.eu).

EASA video Rotorcraft Unintended IMC - Recovery in the Air (youtube.com).

Paolo Dal Pozzo video Electrical Wires Awareness | Feed | LinkedIn.

EASA video Distraction and CFIT.

Video Appesi ad un filo (youtube.com), Prevenire i rischi nel volo a bassa quota, Provincia Autonoma di Trento, Italy.

EASA video The Importance of Wearing Helmets when Flying a Helicopter (youtube.com).

Leonardo Helicopters video Automation and Flight Path Management (youtube.com).

EASA video Unanticipated Yaw (youtube.com).

EHEST video Degraded Visual Environment and Loss of Control.

well done and good job. TEM is the right approach for increasing safety in the opertation. I spent my time teaching that during my courses.

Thanks, Stefano.

Pleased to read that, hoping that this article, illustrations and references will be useful four your courses.

Please log in or sign up to comment.